The API-to-MCP Debate Is Really About Agent Experience

In the AI engineering community, there’s this interesting hot take going around: auto-generated MCP servers that simply wrap REST APIs create poor agent performance. The main concern is that these APIs were originally designed for humans or SDKs, not for agents. When you expose them “as-is,” you get tool overload, wasted reasoning cycles, and confused models.

There’s definitely truth to this. I’ve worked with APIs that completely overwhelm agents, especially with older LLMs. Even with current models, a large surface area of tools can push them to wander rather than act decisively. That said, I’m not fully convinced that API-to-MCP is inherently flawed. My position is more nuanced. I’ve quipped “maybe your API is just bad,” but my fuller thought is that it has less to do with whether an API is good or bad and more to do with what kind of experience we want an agent to have.

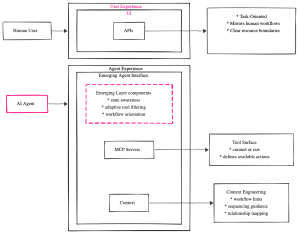

The reality is that nearly everything about AI engineering is fairly new, including our approaches to designing agent experience. I don’t know if there’s an official term for “Agent Experience” yet, and I’m not trying to coin one here. I imagine someone somewhere is already thinking about Agent Experience (AX?) as a new design discipline that sits beside the traditional UX we’ve built for humans. And refocusing our attention on AX helps us move beyond blanket prescriptions toward a better understanding of when API-to-MCP works and when it doesn’t.

Why Some API Surfaces Fail When Mapped Directly into MCP

The clearest failure mode happens when someone points an MCP generator at a very large, SDK-oriented API. These APIs often contain hundreds of operations, deeply nested resources, pagination helpers, batch endpoints, and internal administrative actions. They were designed for typed programming languages where developers rely on autocompletion, documentation, and compiler checks. They were not designed to be reasoned over by a language model.

If you expose this entire surface directly to an agent, the model has too many choices. Tool selection becomes noisy, the agent explores irrelevant operations, and the number of back-and-forth calls grows. In these situations, where no one intentionally designed for the agent’s experience, the critique is valid. It doesn’t surprise me that a design inherited from assumptions that only make sense for developers may not work well for agents.

But Not All APIs Look Like SDKs

Many real-world APIs are much smaller and built to mirror the task flows that humans perform through a UI. These UI-shaped APIs tend to be pragmatic and intuitive. They have just enough operations to support the interface without producing an overwhelming number of choices. When an agent’s role resembles a task a human might perform in the product, these UI-shaped APIs often align well with what the agent needs.

This is where API-to-MCP becomes an elegant, low-friction pattern. The API already expresses the steps in a workflow: one operation to create something, another to update it, another to attach related items, and another to finalize the task. There’s no obscure domain model to infer, no arbitrary distinctions to decode. The agent can reason about the operations the same way a human would if they were using the UI.

A Concrete Example: My Reporter Application

I saw this firsthand while building my Reporter application. The API behind Reporter was originally structured for a simple UI: create a report, add findings, attach actions, leave comments, and update status. It wasn’t large, and it wasn’t designed as a formal SDK surface. It simply mirrored how a human completed reporting tasks.

When I exposed that API through MCP, the agent handled the full workflow with ease. It created reports, added findings, attached actions to each one, and inserted comments in relevant places. It understood how to reference IDs returned from previous calls and could chain those operations effectively. I didn’t have to invent agent-specific abstractions or redesign anything. The shape of the API already matched the shape of the work.

When API-to-MCP Is Appropriate

API-to-MCP is a valid and often effective pattern when the API surface is small and corresponds to meaningful tasks, when the agent’s responsibilities resemble human workflows, when resource boundaries are clear and easy to reason about, and when operations compose naturally. It also works well when the agent doesn’t need hidden backend capabilities and when we can support the agent with context that explains relationships or expected sequences.

This is when you can introduce agentic value immediately with what you already have. If the API is already a clean representation of domain capabilities, use it. Investing in API design pays dividends twice. A well-structured API serves your human users through the UI, and it serves your agents through MCP. The same clarity that makes an API pleasant for frontend developers to work with makes it navigable for an agent. If your API is a mess, both audiences suffer. If it’s clean, both benefit.

The Real Question: What Experience Should the Agent Have?

The success or failure of API-to-MCP is not determined by whether the API was created for humans or for SDKs. The key question is whether the API surface supports the experience we want the agent to have.

Humans have UX. Agents need AX. UX is supported and expressed through the UI—the visual layer that guides users through interactions, constrains their choices, and provides feedback. AX needs its own supporting structures, but we don’t yet have a fully developed equivalent of the UI for agents. What we have is MCP, which exposes capabilities and schemas, but doesn’t actively guide the agent through workflows the way a UI guides a human.

In the absence of that guiding layer, a smaller, more directed API surface compensates by reducing cognitive load. It limits the agent’s choices and makes the workflow clearer through the shape of the tools themselves. This is exactly what I observed with my Reporter application. The API was clear enough that the agent could navigate the workflow without needing additional guidance structures. The tool surface itself provided enough direction.

Designing AX means asking thoughtful questions. Does this agent work more like a human completing a task? Or is it acting as a system-level orchestrator? Does it need broad domain coverage or a narrow, purpose-built surface? Does it need to understand relationships across resources, or will those be supplied as context? These decisions shape whether an existing API is enough, or whether we need a curated agent-native layer.

A real Agent Experience guiding layer might look more like:

Workflow orchestration hints

Contextual tool filtering

Sequential guidance

State awareness that limits what’s shown when

Context engineering is a major part of AX as well. It includes how we prime the agent, guide its sequences, and help it interpret responses. Good context complements the tool surface, working together to shape the agent’s understanding and behavior. This deserves its own deeper discussion, but for now, it’s important to recognize context as a key component of agent experience design.

Looking Forward

API-to-MCP should not be dismissed by default. Yes, some APIs are too broad or too developer-oriented to expose directly. But others map precisely to the tasks we want agents to handle. A poor experience in MCP is not evidence that the pattern is inherently flawed. It might indicate API design issues that humans feel too, or it might mean that the agent deserves a different interface altogether.

As AX becomes a more mature discipline, the question will shift from “Should I wrap my API?” to something more architectural: “Does my API already represent the work I want this agent to do?” When the answer is yes, API-to-MCP can be a clean and effective solution for that particular agent’s needs. When the answer is no, we can design agent-native layers that help the agent understand the domain more clearly.

But the tool surface is just one piece of agent experience. Context engineering, workflow guidance, state management, and other dimensions of AX are still emerging areas of thought. We’re early in understanding how to design well for agents, and there’s room for experimentation and new ideas.

Either way, our goal is to create environments where agents can act with increased reliably, interpretably, and purpose. Thinking deliberately about agent experience gives us a framework to make those decisions with confidence.